Subtotal: $480.00

Inflation is the problem

“Going up in 50-basis-point increments to me makes quite a bit of sense and there’s no reason right now that I see in the economy to pause on doing that in the next couple of meetings”

-Mary Daly, San Francisco Fed President, May 12, 2022

It has become ever clearer that the Federal Reserve sees its sole policy mission right now as getting inflation under control. Every Fed official says so. In fact, financial markets are beginning to understand that the central bank is willing to risk recession — if that’s what it takes to bring price pressures down. We haven’t seen a Fed like this in 15 years. For those of us who saw the Fed dismissing inflation as a threat and resisting pulling out the accommodation even amid excessive hype in asset markets through much of last year, the change of tack is sobering.

How did we get here?

Slowly, yes. But last week’s consumer price inflation report really said it all. It’s the change in the composition of inflation that got us here. The inflation problem has moved from goods to services, particularly housing. And that is a worry for the Fed because those prices are considered “sticky”. This change all but ensures the aggressive response the San Francisco Fed President Daly is warning about.

So, let’s forget about how to engineer a soft landing for now and start figuring out both how far the Fed will have to go, and whether it could be forced into retreat, deploying the so-called “Fed Put.” We’re not there yet. If flirting with recession won’t knock the Fed off course, a further tightening of financial conditions combined with a material slowing should. And, of course, we can’t dismiss an oil price shock due to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

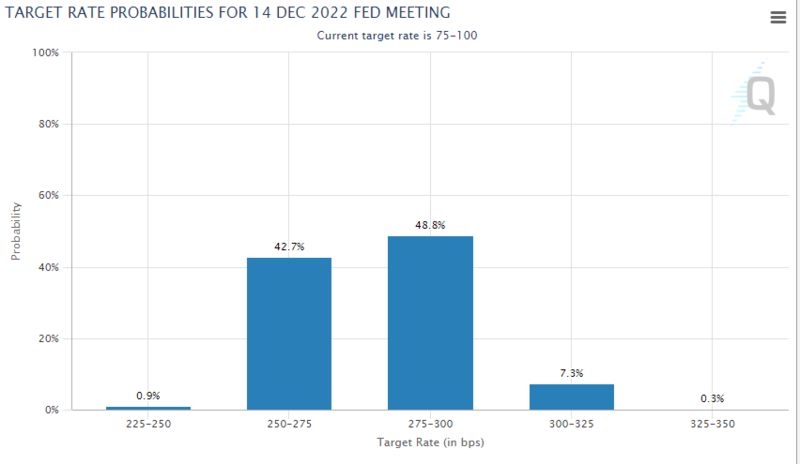

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee meeting in June and the one after that are mostly priced in. It’s by the time we get to the FOMC meeting in September that both the Fed and the markets will be truly put to the test. How inflation behaves during the summer will determine the way forward.

What is a “Fed Put” anyway?

Since the worst case scenario is one where the Fed gets “stopped out” by a slowing economy and worsening financial conditions, let’s work backward from there, from the “Fed Put”. The Put comes in two forms. First, there’s the hard form that involves the Fed buying financial assets or working behind the scenes to cajole banks into lending. That’s rarely used. You have March 2020 (the Pandemic Panic), September 2019 (the Repo Crisis), September and November 2008 (Lehman Brothers and the Great Financial Crisis), September 1998 (LTCM), and October 1987 (Black Monday).

In each of these episodes, financial markets had become so dislocated that not doing something would have threatened the stability of the entire financial system. In these instances, the Fed was forced to act. And, as the Fed’s own website tells you, financial stability is the Fed’s primary function:

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 established the Federal Reserve System as the central bank of the United States to provide the nation with a safer, more flexible, and more stable monetary and financial system.

But when you hear people talk about a Fed Put, they’re usually not talking about these episodes.

There’s a second, broader set of circumstances where the Fed sees the economy decelerating rapidly and eases policy to keep tightening financial conditions from adding to that deceleration. There are many examples of this.

Get 5 years of The WSJ and Barron’s digital news for and save 77% Off

Here’s one. In October 2018, Fed Chair Jerome Powell suggested many more rate hikes were to come. And he said

“We may go past neutral. But we’re a long way from neutral at this point, probably.”

The markets didn’t like this at all. They promptly sold off and continued down for two months, reaching a bear market crescendo on Christmas Eve 2018.

But by Jan. 4, 2019, Powell had changed his tune. When speaking in Atlanta before the American Economic Association, he said the Fed is “always prepared to shift the stance of policy and to shift it significantly”. By July 2019, the Fed was actually cutting rates, not raising them. And by March 2020, with markets melting down due to the pandemic, rates went to zero. That’s the Fed Put in action.

Credit spreads were a good proxy for the Fed Put

So what triggers it?

Buy Barron’s Digital News 5-Years Subscription $59

I take Powell at his word. It’s not that the Fed was stepping in specifically to save equity markets. The central bank saw a broader deceleration in the economy and tightening of financial conditions and decided to pivot. I would also suggest the change in financial conditions that mattered most was not in equities, it was in credit. In that same Atlanta speech Powell identifies when the last Fed Put was:

With the muted inflation readings that we’ve seen coming in, we will be patient as we watch to see how the economy evolves, but we’re always prepared to shift the stance of policy and to shift it significantly if necessary. I’d actually like to point to a recent example when the committee did just that, in early 2016.

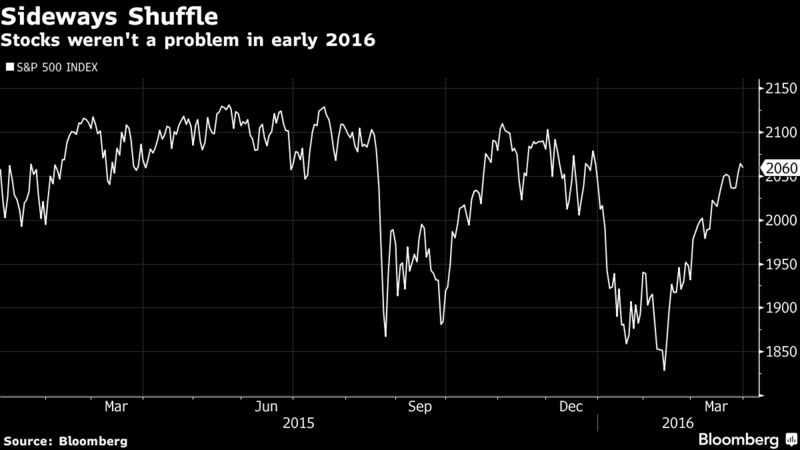

In 2015, stocks traded mostly sideways. So, the Fed didn’t go from tightening to a full year’s pause because of the stock market.

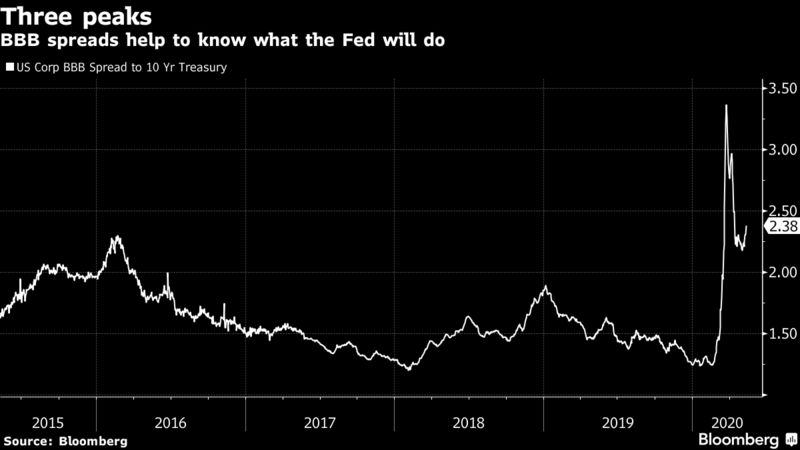

The key change in financial markets in the period leading up to early 2016 was in credit. Triple B credit spreads show you when the last three Fed Puts were executed. The first was in early 2016 after the shale oil market collapse, the second in early 2019 due to the Fed’s tightening and the third in March 2020 because of the pandemic.

In each case, credit distress in high-yield bonds, the lowest-rated companies, had seeped into the investment grade market. And that caused BBB, the lowest-rated investment-grade credits, to sell off and spreads to rise. In effect, the selloff in BBB credits was a signpost of financial conditions tightening enough and overall economic growth deteriorating enough to imperil the access to credit of even safer investment grade companies.

Buy Bloomberg News Digital Subscription for 5-Years Save 70% Off

By the numbers

189 basis points

The peak in BBB spreads on Jan 3, 2019

This time is different

Back in 2019, the Fed’s change in tack had its effect. In fact, the peak in BBB spreads was the night before Powell’s Atlanta speech. And it was only because of the pandemic that they spiked in February 2020. In short, one could reasonably argue the US economy was headed for a soft landing when the pandemic took hold.

Today, BBB spreads are not yet as high as the peaks of the last three episodes, but they are rapidly approaching December 2018 levels.

Here’s the thing though. The environment today is totally different because of inflation. To wit, Fed officials who were waffling about instituting even one rate increase greater than 25 basis points before May are now openly committing to three consecutive outsized hikes. The Fed hasn’t done even two jumbo hikes in back-to-back meetings since 1989.

Listen to what the Fed is saying. Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester recently stated

“We may get another quarter or two of negative growth but that has to happen in order to get inflation down.”

What’s the base case?

So, let’s handicap scenarios for the Fed reversing course:

Get 5 years of The WSJ and Barron’s digital news for and save 77% Off

If inflation comes down, the Fed will ease off the brake and allow the economy to breathe. But from last week’s CPI report, all indications are that this just isn’t happening fast enough.

If the economy falls into a recession, inflation will likely recede, allowing the Fed to ease policy. It’s not a guarantee that inflation goes down in a recession. But demand is lower in a recession by definition. And that should result in an easing of inflationary pressure.

If we have a credit crisis, the Fed would intervene. We know the Fed views financial stability as job #1. Time will tell how bad things would have to get before the Fed steps in but what is clear is that we’re not there yet.

It’s hard to think of the first scenario as a base case given the most recent data. That means we’ll have some combination of scenarios 2 and 3 as a base case.

In terms of a credit crisis, we’re still far from that now. Why? Credit availability is still abundant and defaults haven’t spiked, even among the lowest-rated issuers. In the junk bond space, individual names are seeing big hits to their bond prices after earnings misses. For example, Diebold saw a 40-point drop in a single day just recently. But that’s just an example of a jittery market. It’s not systemic. It’s not a crisis. So we should expect at least the next two 50-basis point hikes to happen.

And then we’ll be waiting on tenterhooks in August and September as the data come in. If inflation is sticky, expect more of the same medicine in September. You might even see the Fed talk about 75 basis-point hikes, if the data are bad enough.

But where will spreads be after two more hikes and the prospect of more to come? That’s a difficult question to answer. We did get to BBB spreads well over 200 basis points without a crisis in 2016. So there’s probably room to run. The disconcerting bit is that we know crises are unpredictable. They are slow-burning events, followed by a bang, a crystallization event where everything becomes chaotic.

Here’s why September matters

Last week, equity market volatility was more than double the pre-pandemic levels. The Nasdaq 100 was already down nearly 30%. The dollar was at a near two-decade high, wreaking havoc on emerging markets borrowers and the profits of S&P 500 companies alike. If the year ended today, it would already be the worst year for Treasury returns on record.

And none of that has shaken the Fed’s conviction to fight inflation.

Political pressure and the need to preserve institutional credibility are too great. The Fed is compelled to increase rates until inflation comes down measurably, say to 4%— even if that risks a recession or a market meltdown. Mester’s comments tell you that.

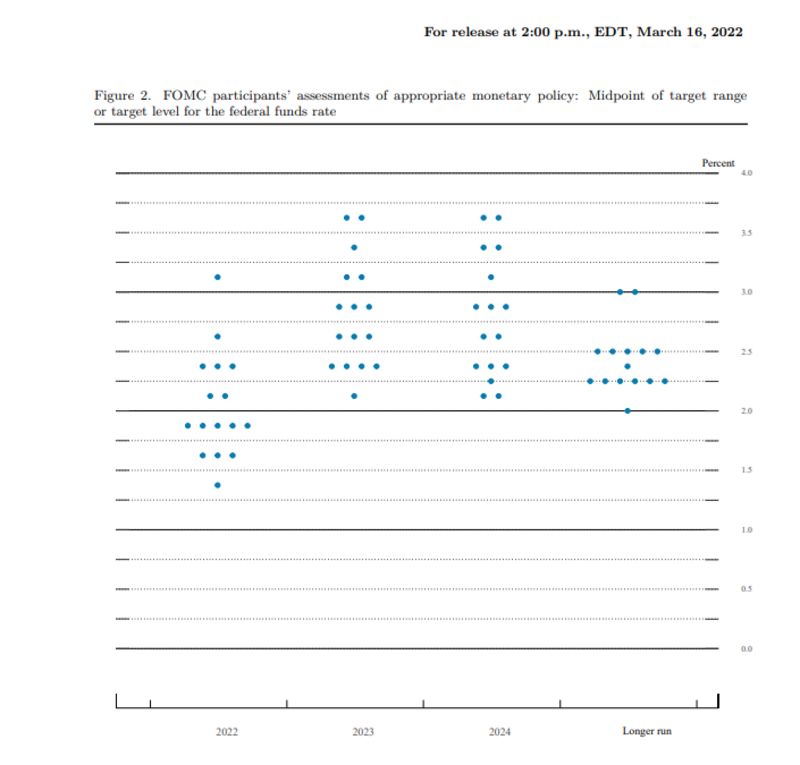

Now, take a look at the FOMC’s last assessment of appropriate monetary policy, the so-called dot plot. It tells you where each Fed official thinks policy should be and gives us a guide into both what they are going to do next and what they think the terminal Fed funds rate will be when they finish raising rates.

The terminal rate from this March dot plot is 2.75 — 3.00% sometime by the end of 2023. And the median dot shows Fed funds at 2% at year end 2022. But that’s only 100 basis points away. Since officials are preparing us for that much tightening in the next two meetings alone, clearly the dot plot to be released in June and then again in September will be very different.

I see the Fed now moving to 2% by July and at least 2.75% at year end. That’s what’s priced into Fed fund futures too.

The dot plot in June is unlikely to deliver a surprise. But I don’t expect inflation to recede and therefore, the September dot plot could show even more rate hikes.

If you look at mortgage rates and home-buyer sentiment, financial conditions have already tightened considerably.

If traders come back from their August vacation to a Fed poised to continue hiking in 50-basis point increments or even lobbing in a three quarter-point hike, the risk of markets swooning and financial conditions tightening aggressively at that point rises exponentially. Add in a housing market that could come to a halt amid rising mortgage rates and a material slowdown in gross domestic product growth, and you have the makings of a meltdown that could be bad enough to bring back the Fed Put in subsequent months. One can only hope inflation will have decelerated sufficiently by then.

Oh, and before I forget, Bloomberg’s MLIV Pulse is running a survey this week asking readers this very question, what will bring the Fed Put back. Please have a look and answer the questions here.

The Wall Street Journal and Barron's Membership for $480

The Wall Street Journal and Barron's Membership for $480