Economy

It Now Costs $300,000 to Raise a Child

The cost of raising a child through high school has risen to more than $300,000 because of inflation that is running close to a four-decade high, according to a Brookings Institution estimate.

It determined that a married, middle-income couple with two children would spend $310,605—or an average of $18,271 a year—to raise their younger child born in 2015 through age 17. The calculation uses an earlier government estimate as a baseline, with adjustments for inflation trends.

The multiyear total is up $26,011, or more than 9%, from a calculation based on the inflation rate two years ago, before rapid price increases hit the economy, the Brookings Institution said.

Estimated annual family expenses for a child born in 2015

For Muffy Mendoza, high inflation has meant that “boys week” wasn’t in the cards this summer. The gathering, she said, is usually a time for all of the boys in her family—her three sons and their cousins—to get together at her Pittsburgh home. This year, the gathering is too expensive. “It costs a lot to feed almost 10 boys,” she said.

Subscribe today and get 52 weeks of The WSJ Print Edition for $318

Brookings calculated the cost of raising a family based on a 2017 estimate from the Agriculture Department. The estimate covers a range of expenses, including housing, food, clothing, healthcare and child care, and accounts for childhood milestones and activities—diapers, haircuts, sports equipment and dance lessons, among other costs.

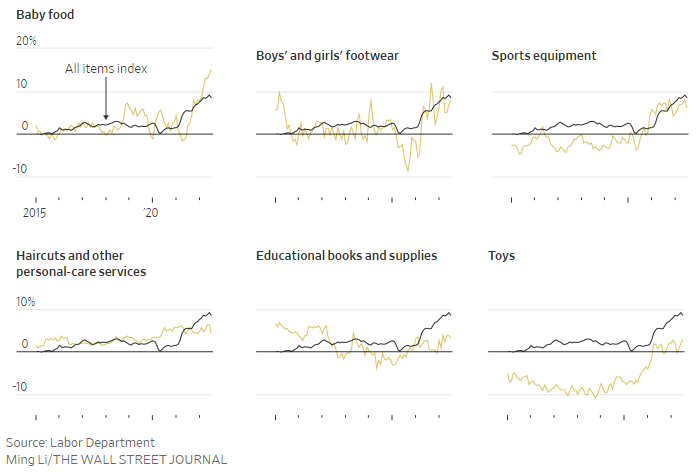

Consumer-price index, 12-month change

“A lot of people are going to think twice before they have either a first child or a subsequent child because everything is costing more,” said Isabel Sawhill, a senior fellow at Brookings. “You also may feel like you have to work more.”

Inflation’s trajectory in the future isn’t clear, Dr. Sawhill said, in part because Federal Reserve efforts to bring the rate down have an uncertain outcome.

“We know it’s very high right now, but we also know that the Fed is stepping on the brakes very hard and that it’s going to come down,” she said. “We don’t know how fast and to what level and how long it will stay somewhat elevated.”

The annual inflation rate eased to 8.5% in July, down from 9.1% the prior month. Gasoline and other energy prices fell from the prior month, but food prices continued to climb. Prices for food at home were up 13.1% in July compared with the year before, the Labor Department said, adding pressure to household budgets.

High prices in the grocery store have led Jennifer Smith to be creative at mealtimes. Meatless Mondays and clean-out-the-fridge Thursdays are new additions to the family’s bill of fare. A turkey sandwich, leftover pasta, and sautéed peppers and onions were all on the menu one Thursday night in the Raleigh, N.C., home.

Buy Bloomberg Digital Subscription 5 Years $89

Mrs. Smith said her grocery bill has rocketed up. She noticed prices for snack foods—Cheez-It and Goldfish crackers, among others—have increased. “Our kids are back-to-school shopping now,” she said. “Everything has gone up. “

Rising expenses for raising a family could disproportionately affect lower-income families, said Dr. Sawhill, who holds a Ph.D. in economics. For a single parent earning $20,000 or $30,000 a year, shelling out the extra funds for a child might be difficult, she said.

Black families are also more exposed to inflation fluctuations, economists say. Researchers from the University of California, San Diego, and the Richmond Federal Reserve Bank showed that Black families experience higher levels of price volatility, which can make it difficult for households to determine how much the money they earn will buy.

To respond to higher prices, people might choose to shop at a more affordable store, but Black households were already shopping at the cheapest nearby store, said Munseob Lee, an economics professor at the University of California, San Diego. He said shoppers could also trade down to lower-quality items, but Black families and lower-income households have little room to adjust.

“There’s nothing left to cut out,” said Mrs. Mendoza, who is chief executive officer of Brown Mamas, a network of more than 6,500 Black mothers in the Pittsburgh area. “We’re cutting off the cable today because we can’t afford it,” she said of efforts to reduce her household’s costs.

Get Barron’s Digital News 5-Years Subscription $69

Tamera Dixon, a Pittsburgh mother of a son, said she is trying to save money, even in her sleep. “Switching cellphone plans, cutting back on eating out, helping your neighbor, buying from your local grocery store, your local farmers market,” Ms. Dixon said. “When you’ve done all those things naturally just to survive, you’ve run out and you’ve exhausted all of that.”

Child care, including nannies, preschools and nursery schools, is one of the greatest costs for most families, said Diane Schilder, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute.

Adrienne Briggs, who runs Lil’ Bits Family Child Care Home, in Philadelphia, has been in the business for decades. It is a family child-care center, where she cares for children on one floor and lives on another. Ms. Briggs, who holds a master’s degree in early childhood education, said her salary isn’t commensurate with her education. She said she makes less than minimum wage, which is $7.25 an hour in Pennsylvania.

Most of the families she serves receive government subsidies, she said. “That actually pays about half of what my true cost really is, and it’s kind of hard to put the true cost onto the families just because of inflation, and even before inflation, just the economy itself.”